Biography

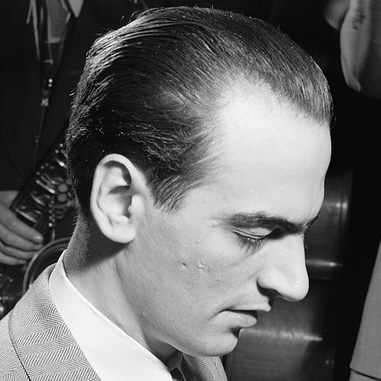

Cecil Taylor was one of the most uncompromising and radical figures in the history of jazz. Born in Long Island City, New York, he began studying piano at a young age and received formal classical training before enrolling at the New England Conservatory. Though deeply versed in European modernism—particularly Bartók, Stravinsky, and the Second Viennese School—Taylor found traditional jazz structures increasingly restrictive, and by the mid-1950s he was already moving toward a highly personal and confrontational musical language.

Taylor’s early recordings, including Jazz Advance (1956), revealed a pianist pushing against harmonic and rhythmic conventions while still engaging with jazz forms. As his career progressed, he abandoned standard song structures almost entirely, favoring long, continuous improvisations driven by density, velocity, and physical intensity. His music often baffled audiences and critics, but it also attracted a devoted following.

By the mid-1960s and early 1970s, Taylor’s recordings had taken on the character of formal artistic statements. Unit Structures (1966) announced a fully realized conception of ensemble improvisation, while Silent Tongues (1974) revealed the maturity of Taylor’s language.

Despite his reputation as an outsider, Taylor seemed to be able to operate the jazz institutional system like an insider. His album 3 Phasis (1978) proudly listed numerous foundation grants and public funding. In 1975 he was voted by critics into the Downbeat Jazz Hall of Fame. Taylor composed for dance companies, collaborating with figures including Alvin Ailey and Mikhail Baryshnikov.

Taylor’s uncompromising stance extended beyond the bandstand. Invited to teach at a major university, he provoked controversy when he failed large numbers of students and resisted institutional pressure to revise grades. This rigidity—admired by some, criticized by others—mirrored the values of his music: total commitment, absolute seriousness, and an unwillingness to negotiate with expectations.

Influences

Cecil Taylor

Cecil Taylor

Contributions to jazz

Cecil Taylor fundamentally redefined what jazz improvisation could be. Rejecting swing feel, functional harmony, and chorus-based forms, he treated improvisation as a continuous process rather than a series of variations over structure. His approach aligned jazz more closely with contemporary classical music by Stockhausen, Messiaen, and Berio.

Contributions to jazz piano

Taylor transformed the piano into a percussive, orchestral instrument. His use of tone clusters, extreme registers, and layered polyrhythms rejected the linear, horn-derived conception of jazz piano that dominated bebop and hard bop. It emphasized textures over lines.

Taylor is Taylor is Taylor. His celebration of self is bound up with a stubbon intransigence… Personality itself is technique. Given Taylor’s holy role as the eternal outer curve of the avant-garde, it isn’t his function to make things easy.

— Gary Giddins, Visions of Jazz

Listen

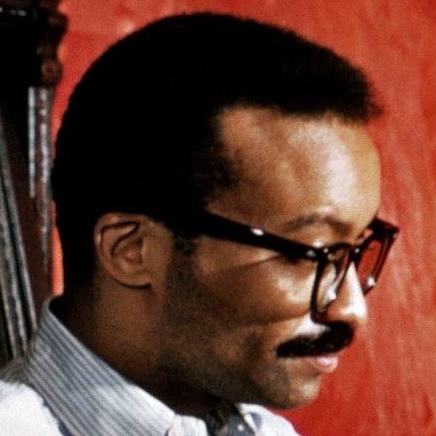

The Embraced concert, recorded live at Carnegie Hall in 1977, brought together two pianists often portrayed as occupying opposite ends of the jazz spectrum: Mary Lou Williams, rooted in swing, blues, and sacred traditions, and Cecil Taylor, the leading figure of the avant-garde.

New York Times review of the concert