Listen

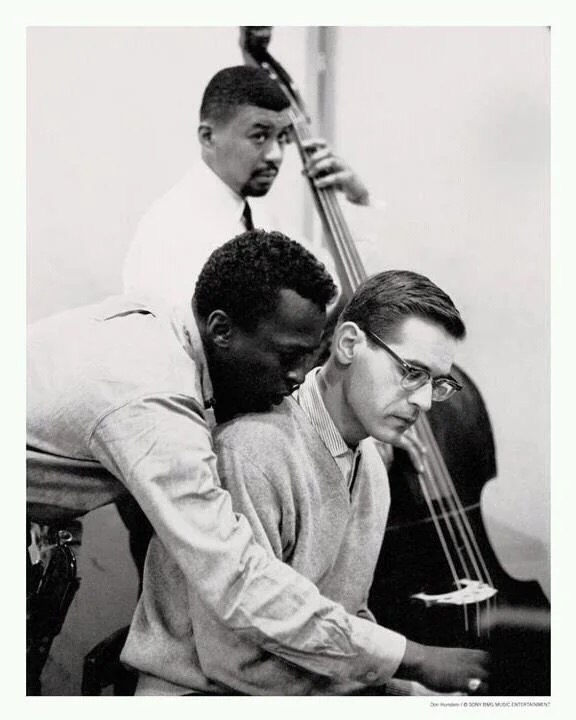

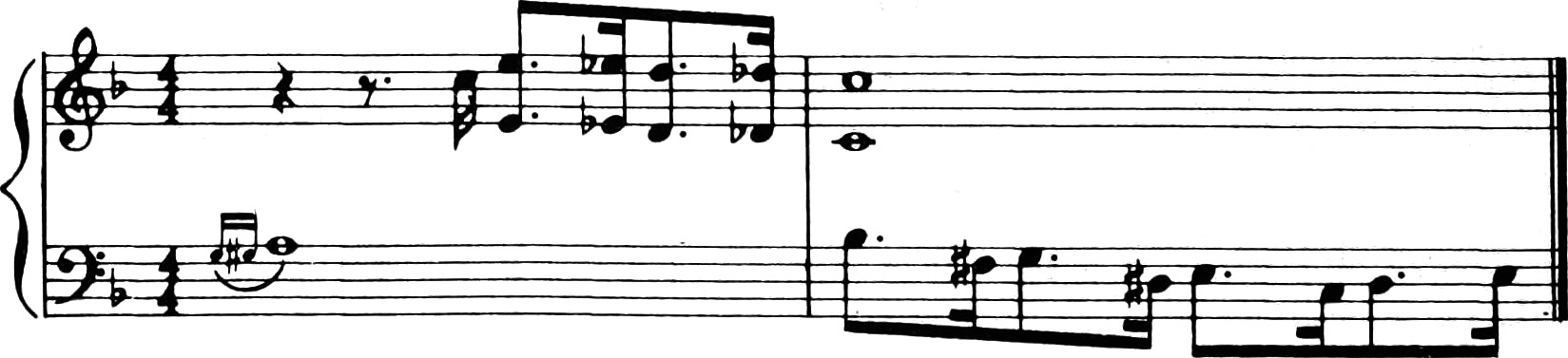

Parisian Thoroughfare (1951)

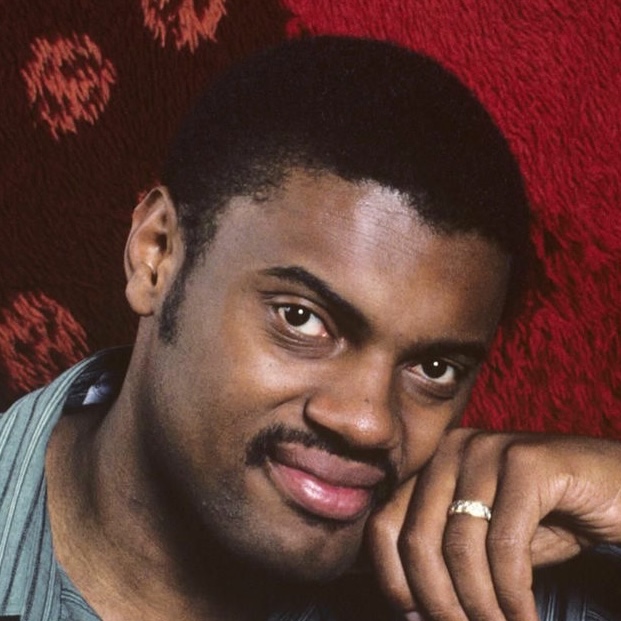

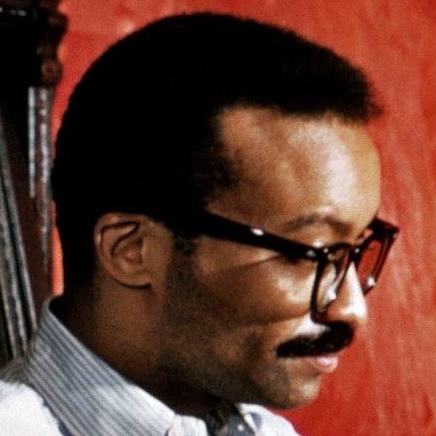

Bud Powell

The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 (The Rudy Van Gelder Edition)

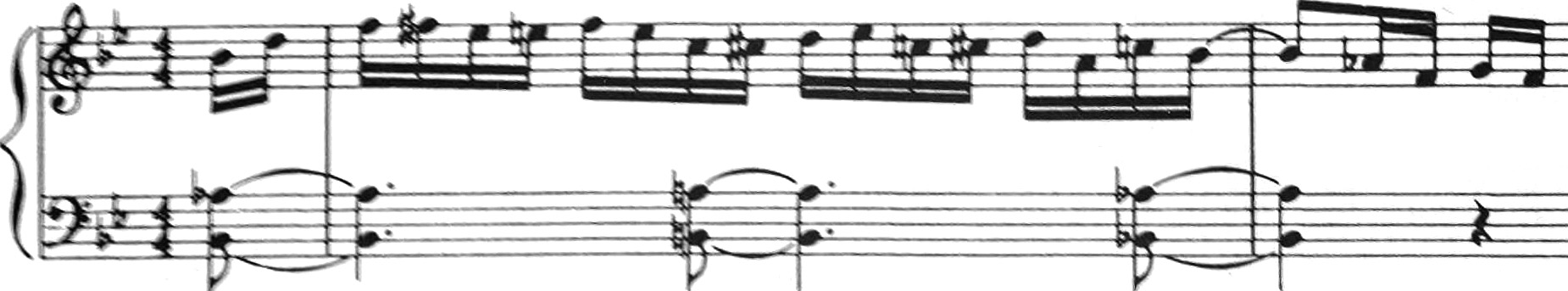

Bebop emerged in the early 1940s as a radical reimagining of jazz, forged in late-night jam sessions at Minton’s Playhouse and Monroe’s Uptown House in Harlem. Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, reacting against the constraints and commercial polish of big-band swing, pursued a faster, more harmonically sophisticated, and more intellectually demanding music. This music was not designed for dancing or mass entertainment; it was a musicians’ music, privileging virtuosity, spontaneous invention, and harmonic fluency.

Charlie Parker’s solo language—with its quicksilver timing, offbeat phrasing, and harmonically adventurous “wrong notes”—was hugely influential. It inspired all instrumentalists in the ensemble to phrase like and match Parker’s speed and elegance.

Listen

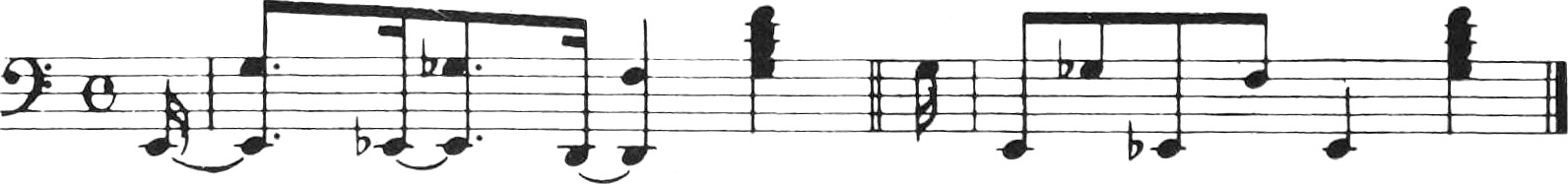

Well You Needn’t (1951)

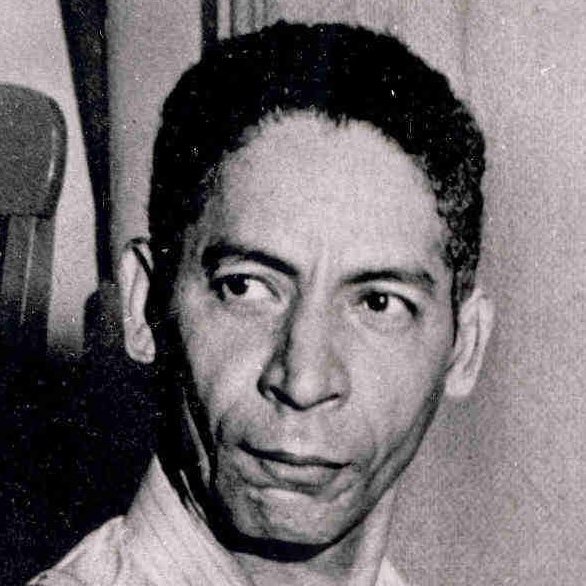

Thelonious Monk

The Genius of Modern Music, Vol. 1

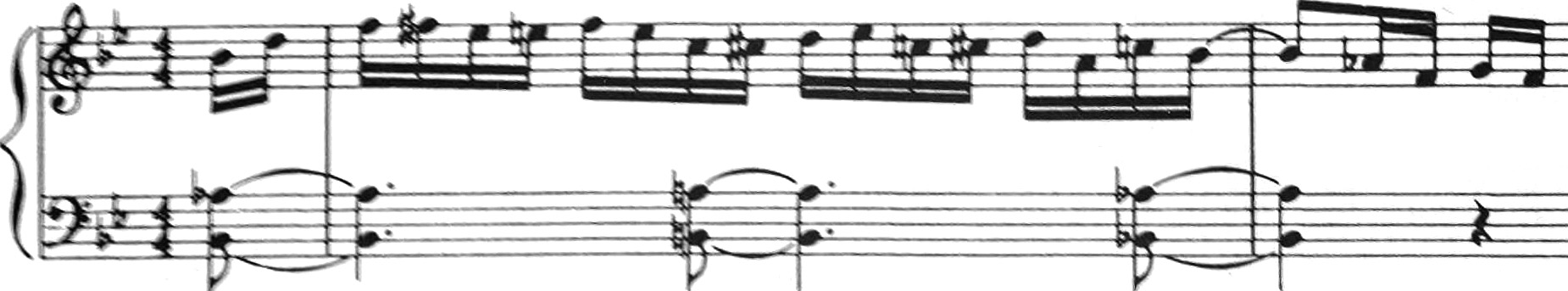

Now, the pianist plays linear, asymmetrical melodies using more non-chordal tones, often ending on them. In slower tempos, notes on the weak part of beats are accented. Instead of maintaining a steady pulse, the left hand plays the barest of intervals to connote the harmony, providing space for the more complex right-hand improvisation, in addition to a countermelody.

Double-, even quadruple-time feeling often appeared in solos, so the tempo of performance felt faster than it was. Articulation and touch became important facets of pianistic tone because pianists wanted the lines to sound more horn-like. Use of pedal was often avoided.

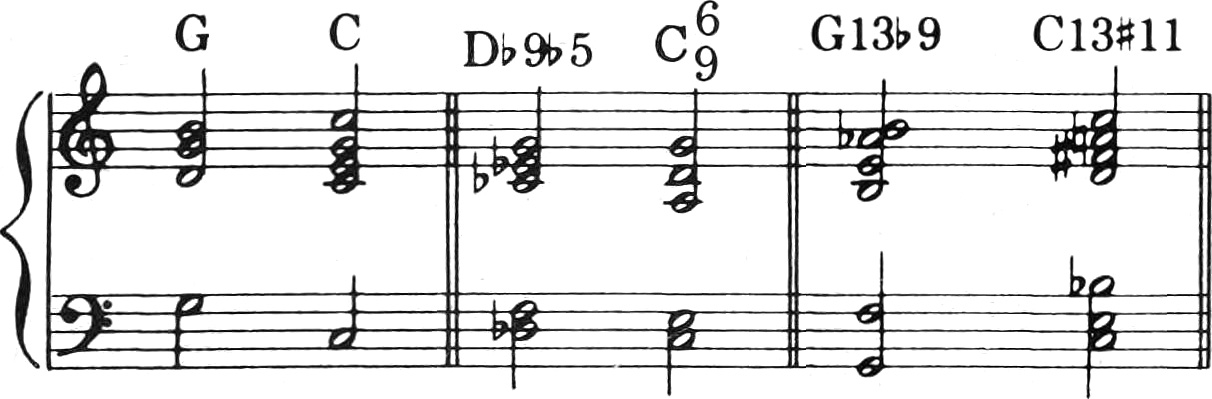

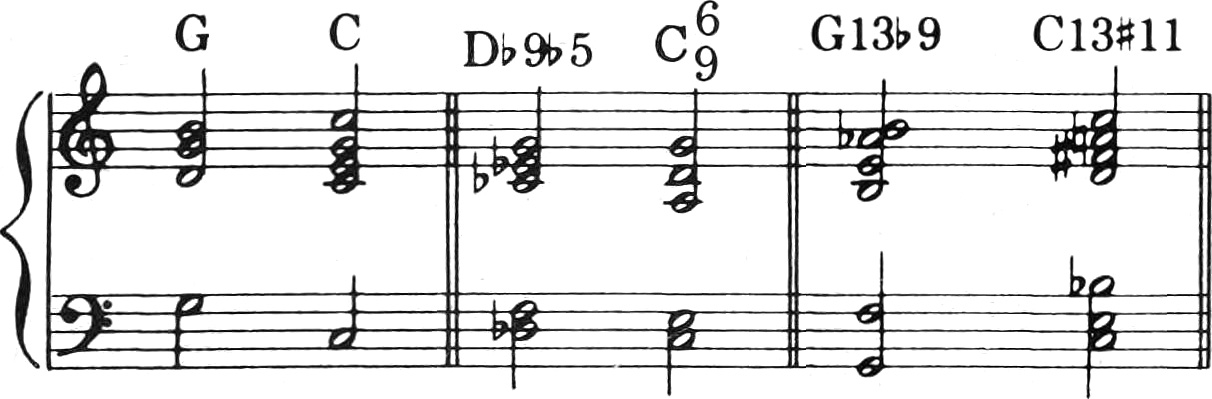

The harmonic language is enriched with altered chords and chord substitutions. The most common one would be the tritone substitution, where dominant sevenths (V7) would substitute the root for its tritone, creating V7b5 chords that eventually became a cliché.

As drummers expanded their rhythmic and coloristic possibilities, pianists had to evolve with them. Comping had to be done using the new syncopated vernacular. To be heard within the ensemble, a locked-hands style of comping emerged to cut through drum accents.

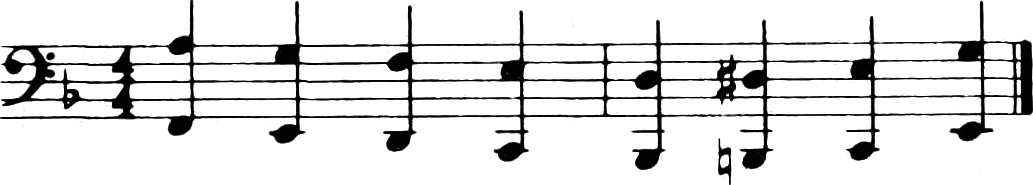

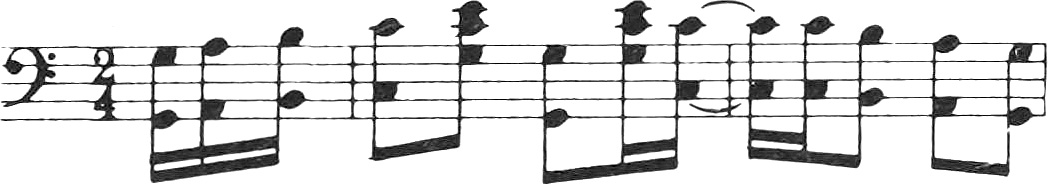

At the same time, bebop intersected with Afro-Latin musical traditions, giving rise to what became known as Afro-Latin jazz. Through figures such as Dizzy Gillespie, who collaborated with Caribbean musicians including Chano Pozo, bebop’s harmonic language was fused with rhythmic systems rooted in clave-based traditions. Rather than swing’s four-beat feel, Afro-Latin jazz emphasized layered, cyclical rhythms and a more static harmonic rhythm. For pianists, this meant adapting bebop vocabulary to repeated rhythmic cells, ostinati, and cross-rhythms—expanding jazz piano’s rhythmic conception well beyond its swing-era foundations.

Listen

Un Poco Loco (1951)

Bud Powell

The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1 (The Rudy Van Gelder Edition)

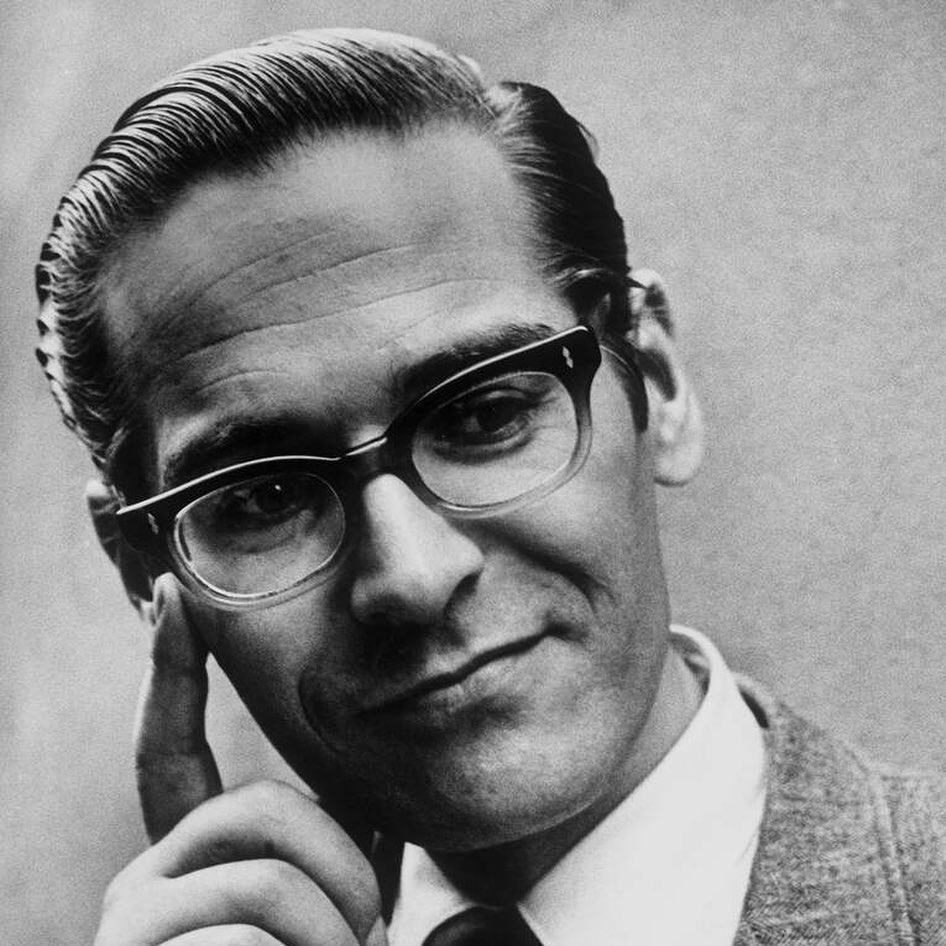

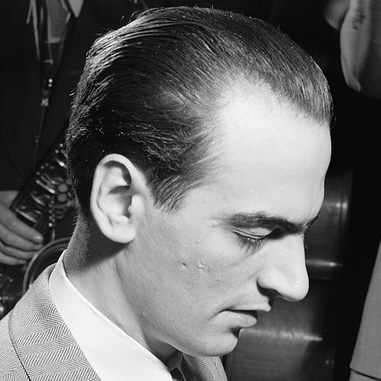

![Portrait of Jack Teagarden, Dixie Bailey, Mary Lou Williams, Tadd Dameron, Hank Jones, Dizzy Gillespie, and Milt Orent, Mary Lou Williams' apartment, New York, N.Y., ca. Aug. 1947 [Gottlieb Collection Assignment No. 338]](/assets/images/gottlieb-338.jpg)