Biography

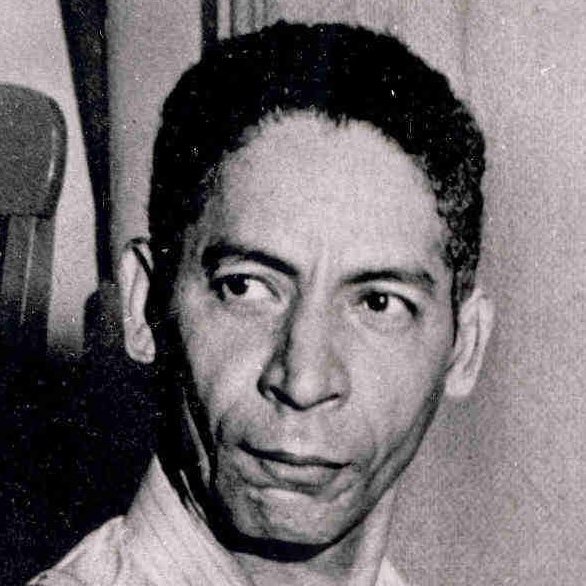

Lil Hardin Armstrong was a pioneering jazz pianist, composer, arranger, and bandleader whose musical leadership and business acumen shaped the early development of jazz in Chicago during the 1920s. When her family moved to Chicago in 1918 during the Great Migration, she took a job demonstrating sheet music at Jones Music Store, where she impressed customers and local musicians with her blues-inflected improvisations on popular songs. That same year, she joined Lawrence Duhé’s New Orleans Creole Jazz Band, becoming one of the few women in Chicago’s male-dominated jazz scene and earning the nickname “Hot Miss Lil”. She joined King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band in 1921, where she met Louis Armstrong in 1922 when Oliver brought him to Chicago as second cornetist.

Recognizing Louis Armstrong’s extraordinary talent, she became the driving force behind his career, convincing him to leave Oliver’s band in 1924 to join Fletcher Henderson in New York, and later organizing the legendary Hot Five and Hot Seven recording sessions with herself as pianist and arranger. She played a pivotal role as arranger and facilitator for the groundbreaking King Oliver Creole Jazz Band recordings of 1923, helping musicians who could not read or write music notate and copyright their compositions. Throughout the 1920s, she was one of several prominent African American women leading bands in Chicago, including her own Dreamland Syncopators.

Armstrong continued her multifaceted career as a bandleader, composer, and Decca Records house pianist throughout the 1930s and 1940s. She performed internationally through the 1950s and 1960s, collaborating with artists including Alberta Hunter and Sidney Bechet. On August 27, 1971, she collapsed while performing “St. Louis Blues” at a televised memorial concert for Louis Armstrong in Chicago and died shortly after at age 73.

Influences

Contributions to jazz

Lil Hardin Armstrong played a pivotal role in early jazz by serving as arranger and facilitator for the groundbreaking King Oliver Creole Jazz Band recordings of 1923, the first extensive recordings by a Black jazz ensemble. Most of the musicians she worked with could not read or write music, and she played an essential role in helping King Oliver and Louis Armstrong notate and copyright their compositions, enabling them to earn royalties from their work. As pianist and musical director for Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five and Hot Seven sessions from 1925 to 1927, she provided the rhythmic foundation that helped create some of the most influential jazz recordings in history. Her ability to both read music fluently and improvise with exceptional ear allowed her to bridge the gap between formally trained musicians and those who played by instinct.

As a composer, Armstrong created numerous jazz standards including “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue,” “Just for a Thrill” (later a hit for Ray Charles in 1959), “Doin’ the Suzie-Q,” “Two Deuces,” “Don’t Jive Me,” and “Bad Boy” (recorded by Ringo Starr in 1978). She was one of several prominent African American women leading bands in 1920s Chicago, including her own Dreamland Syncopators, and later led both all-female and mixed-gender orchestras. During the 1930s, she worked extensively as a Decca Records house pianist, accompanying numerous blues and jazz artists and leading her own recording sessions that produced over twenty selections. Her fifty-year career and presence as a woman in leadership roles helped pave the way for future generations of female jazz musicians in an overwhelmingly male field.

Contributions to jazz piano

Armstrong’s piano style was characterized by a hard-pounding, rhythmically solid approach that emphasized all four beats, which helped compensate for the absence of bass in early jazz ensembles. Her playing reflected the traditional role of pianists in New Orleans-style groups—providing rhythmic accompaniment rather than flashy solos. Though sometimes dismissed for being less innovative than later pianists like Earl Hines, her unorthodox early training gave her a distinctive touch and her strong sense of time made her highly valued by bandleaders. She demonstrated her range as both a stride pianist and swing-era performer, and her ability to embellish sheet music with blues-tinged improvisations showed her versatility. As arranger and musical director, she shaped the sound of numerous seminal recordings, organizing sessions, transcribing compositions, and providing the structural framework that allowed soloists to shine.

Adam Bravo transcribed Armstrong’s solo on “You’re Next”.

Bay-Area based pianist Charles Chen processed the Hot Five recordings to bring Armstrong’s playing more to the foreground.

She was the brains of the band.

— James Dickerson, Just for a Thrill