Biography

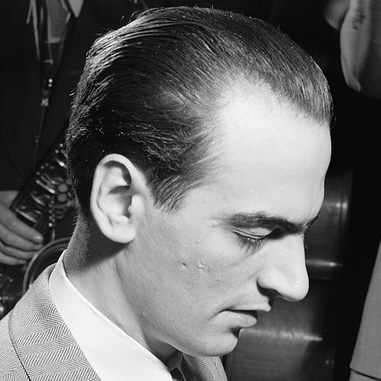

A native of Duquesne, Pennsylvania, Earl Hines grew up as the son of a cornetist, and stepson of a church organist. Hines studied formally but was deeply influenced by ragtime and stride pianists of the era, which shaped his early approach to jazz piano. By his teens, he was already performing professionally in local venues.

In the 1920s, Hines moved to Chicago, where he became a key figure in the burgeoning jazz scene. He played with the Carroll Dickerson Orchestra, where he met Louis Armstrong, and the two formed an immediate musical kinship. By 1927, Armstrong had taken over Dickerson’s band with Hines as musical director, and the two began recording together in a partnership that would yield some of the most celebrated sides in early jazz history. His piano style quickly attracted attention for its rhythmic energy and inventive use of octaves, which earned him the nickname “Fatha.”

Hines went on to lead his own big band for two decades, most notably as the house band at Chicago’s Grand Terrace Ballroom from 1928 through the 1930s, where nightly radio broadcasts carried his music to a national audience. In the early 1940s he assembled a forward-looking orchestra that included bebop pioneers Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie alongside singers Sarah Vaughan and Billy Eckstine—though wartime recording bans meant the band was never captured on record.

After the big band era faded, Hines played with Armstrong’s All Stars, fronted a Dixieland group in San Francisco, and was nearly forgotten by the early 1960s. A series of solo recitals arranged by writer Stanley Dance at New York’s Little Theatre in 1964 triggered a stunning comeback, and Hines performed and recorded prolifically for the remainder of his life. He died on April 22, 1983, in Oakland, California, at age 79.

Influences

Contributions to jazz

Earl Hines occupies a singular position in jazz history as the bridge between its earliest piano styles and the modern era. Before him, pianists in jazz largely served as rhythm providers, either in the New Orleans tradition or in the Harlem stride style pioneered by James P. Johnson and Fats Waller. Hines was the first major pianist to break the mold: he fractured the stride rhythm with unexpected accents, suspended time during daring solo breaks that engaged both hands in simultaneous flights across the keyboard, and returned to the beat without missing a pulse. This rhythmic daring, combined with his melodic approach to improvisation, established the piano as a genuine soloist’s instrument within jazz, not just an accompanist or timekeeper.

Beyond his personal artistry, Hines served as a crucial incubator for bebop and modern jazz. Duke Ellington observed that the seeds of bop were present in Hines’s piano style, and his early 1940s big band with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Sarah Vaughan is widely regarded as the first bebop orchestra. His influence radiated outward through Chicago’s radio broadcasts during the 1930s and his many recordings. Hines changed the style of the piano, and one can trace the roots of virtually every modern jazz pianist back to the path he blazed.

Contributions to jazz piano

Hines’s defining innovation was his “trumpet style,” a technique in which his right hand played melodic lines doubled in octaves, producing a clear, ringing tone that could cut through even a full big band, much the way a brass soloist would project.

He layered this with frequent use of tremolo to simulate the vibrato of a horn, and employed “walking tenths” and rhythmic arpeggios in the left hand rather than the predictable stride pattern. The result was an entirely new sonic palette for the piano: percussive yet singing, rhythmically unpredictable yet always swinging. Hines himself credited the practical challenge of being heard in large ensembles as the catalyst for developing octave playing, but the style went far deeper than volume — it gave jazz piano a linear, improvisational voice.