Biography

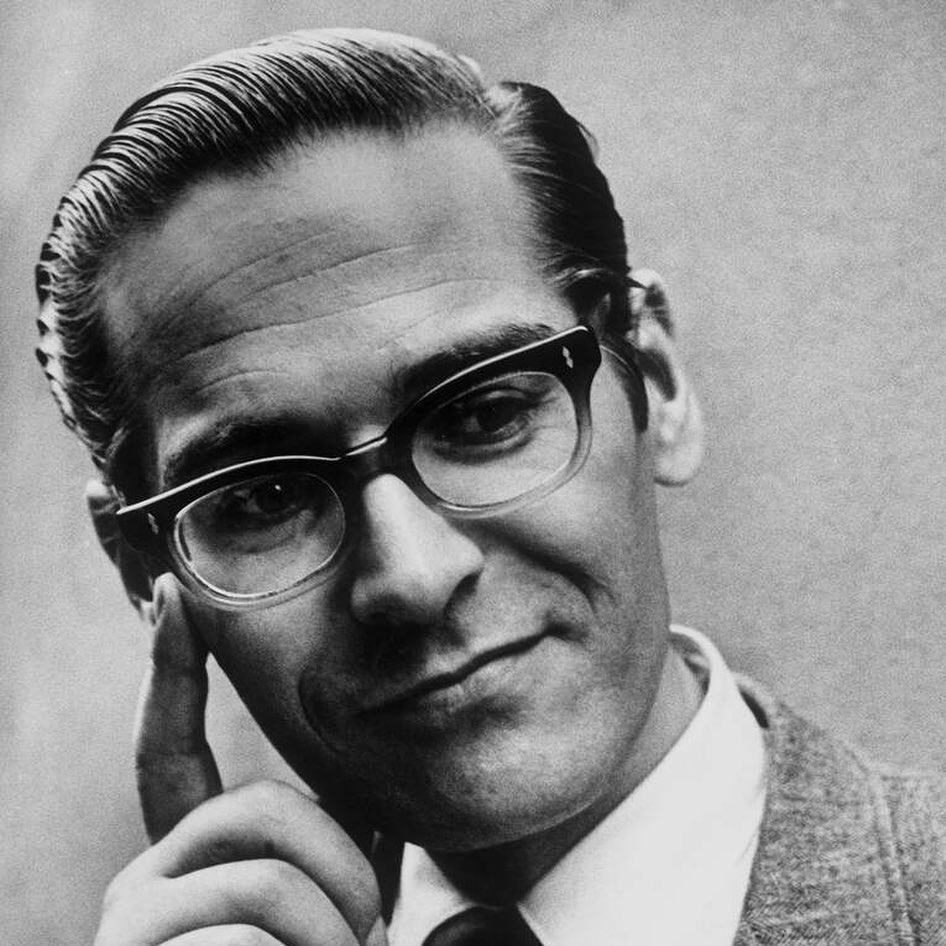

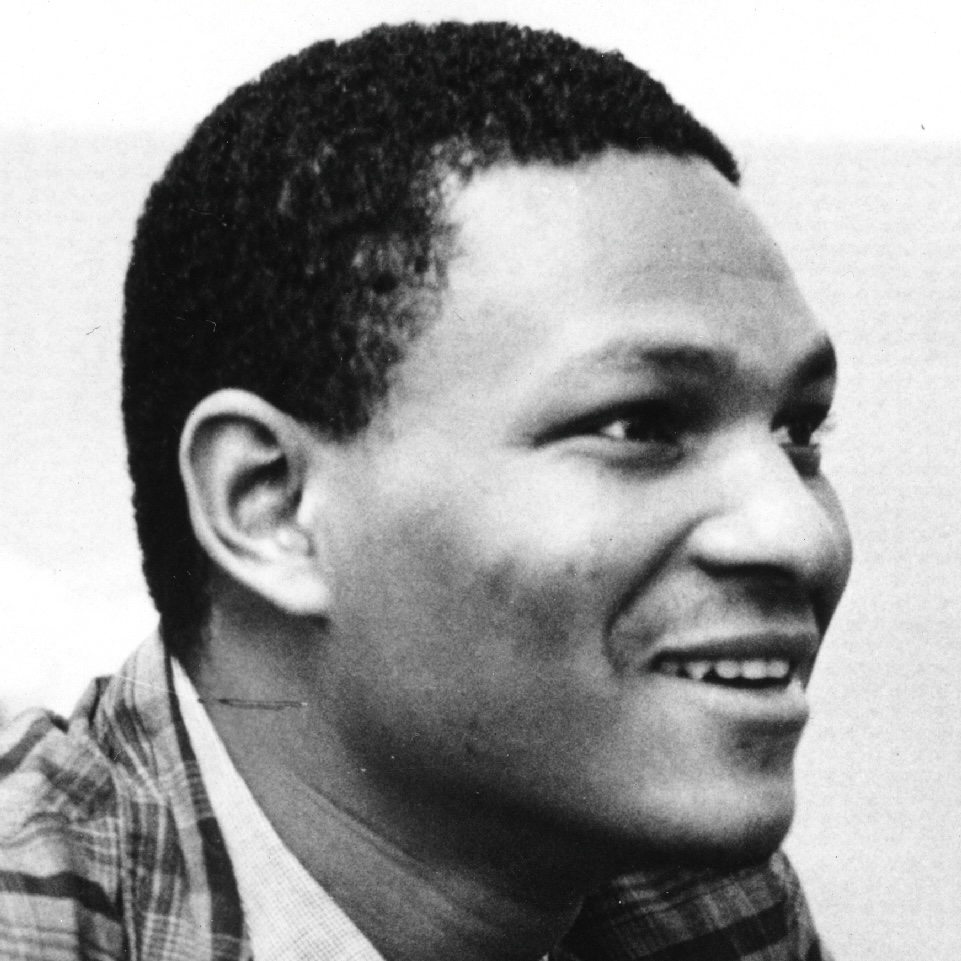

Bud Powell was born in New York City into a musical family and trained seriously in classical piano from early childhood. As a teenager he entered the emerging bebop scene at Minton’s Playhouse, where he came under the mentorship of Thelonious Monk and quickly distinguished himself through extraordinary technical facility and a radically modern improvisational voice.

Powell’s career was repeatedly disrupted by severe mental illness, exacerbated by a brutal beating by police in 1945 and subsequent institutionalizations that included electroconvulsive therapy. Despite these interruptions, his most productive years—roughly 1949 to 1951—produced recordings that defined the sound of bebop piano. He later lived and performed in Paris before returning to the United States in declining health. He died in 1966 at the age of forty-two.

Though his life was marked by instability, Powell is remembered by fellow musicians as the definitive pianist of the bebop era.

Influences

Contributions to jazz

Bud Powell was the first pianist to fully internalize and project the language of bebop, translating the innovations of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie into a convincing and idiomatic piano style. Before Powell, bebop was primarily a horn-driven music; after Powell, the piano stood as an equal melodic voice within the movement.

Inspired by Earl Hines and Art Tatum, his playing demonstrated that bebop’s harmonic complexity, rhythmic volatility, and long-form melodic thinking could be sustained on a keyboard without reliance on earlier swing or stride conventions. In doing so, Powell helped solidify bebop not just as a style, but as a complete musical system adaptable across instruments.

Contributions to jazz piano

Powell permanently transformed jazz piano by redefining the roles of the two hands.

- His right hand carried extended, horn-like melodic lines—fast, linear, and harmonically precise—modeled on Parker’s improvisations.

- His left hand abandoned stride and dense swing-era chordal patterns in favor of sparse shell voicings or silence, reducing harmony to its essentials.

One musician, after hearing Powell’s solo rendition of “Just One Of Those Things”, stated that “He almost plays off the end of the piano.”1

This approach lightened the piano texture and allowed unprecedented speed, clarity, and forward momentum. Powell’s method became the standard vocabulary of modern jazz piano.

[Bud Powell] was another Tatum, only much more modern, adding to what Tatum had already laid down for the classical pianists and for everybody. I always say Tatum was the master and that Bud developed what the master left.

— Erroll Garner

If I had to choose one single musician for his artistic integrity, for the incomparable originality of his creation and the grandeur of his work, it would be Bud Powell. He was in a class by himself.

— Bill Evans

He was the foundation out of which stemmed the whole edifice of modern jazz piano.

— Herbie Hancock